* The preview only shows a few pages of manuals at random. You can get the complete content by filling out the form below.

Description

Youth Smoking Status: Perceptions Versus Measurements Todd L. Bottom, BA; Monica L. Adams, MPH; Leonard A. Jason, PhD; Annie Topliff, MA Objective: To determine whether youths who have smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days perceive themselves as smokers. Methods: Sensitivity and specificity for 3 classifications were analyzed and compared to youths’ perceptions of smoking status. Results: The common criterion of having smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days reflected youths’ perceptions of their smoking status with modest accuracy al-

T

he Healthy People 2010 Midcourse Review reports that the number of high school students who smoke has declined in recent years and that the proportion of high school students who report past 30-day use of tobacco has achieved 68% of the targeted change.1 Although smoking prevalence rates declined from the late 1990s to 2004, the decline has leveled off in recent years, and youth smoking prevalence rates are not meeting the goals outlined within the HP 2010 project.1,2 For these prevalence projections, it is critically important to have measures of youth smoking that are reliable, valid, and consistently used

Todd L. Bottom, Research Assistant; Monica L. Adams, Project Director; Leonard A. Jason, Principal Investigator; Annie Topliff, Community Relations Manager, all from DePaul University, Center for Community Research, Chicago, IL. Address correspondence to Mr Bottom, Research Assistant, DePaul University, Center for Community Research, 990 W Fullerton Ave, Suite 3100, Chicago, IL 60614. E-mail: tlbottom@yahoo.com

760

though adding a second criterion of having also smoked 100 or more cigarettes in a lifetime more accurately reflects youths’ perceptions of their smoking status. Conclusions: Youths frequently determine smoking status based on behavioral criteria that differ from the standard criterion of 30-day point prevalence. Key words: smoking, tobacco, youth, status, perception Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):760-768

among investigators. Additionally, understanding whether youths who smoke perceive themselves as smokers may be important in determining the effectiveness of prevention and cessation programs. Researchers often use the operational definition of 30-day point prevalence (ie, having smoked on at least 1 of the past 30 days) when classifying youths under the age of 18 as smokers. This method of classification has been recommended by an expert panel to be used as a primary outcome measure for determining youth smoking prevalence, and it is probably the most common classification used to determine smoking status of youth under the age of 18.3,4-7 However, this method of classifying youths as smokers may capture many youths who have simply experimented with cigarettes recently, but have not yet developed a smoking habit. Additionally, a different adult operational definition of current smoker is used to classify young adults aged 18-24 as current smokers, which accounts for both current (ie, past 30 days) and lifetime (ie,

Bottom et al

smoking 100 or more cigarettes lifetime) cigarette use.8 Because the operational definition used to classify youths as current smokers differs from the definition used to classify young adults as current smokers, it is difficult to determine accurate prevalence rates as young people transition from youth to adulthood. It is important to ensure that operational definitions and methodologies used between studies remain consistent because differences in operational definitions used to measure aspects of smoking may produce inconsistent results between studies.9 As an example of how differing operational definitions can affect prevalence estimates between studies, Arday and colleagues reported that the criteria used to determine smoking status were changed between the 1989 and 1992/ 1993 administrations of the Current Population Survey (CPS).10 Prior to 1992, both the CPS and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) classified respondents as current smokers if they answered “Yes” to the questions “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your lifetime?” and “Do you smoke now?” In 1992/1993, the wording of the 2 questions in the BRFSS remained the same, while the CPS changed the wording of the second question to ”Do you smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” Respondents who reported smoking “every day” or “some days” were considered to be current smokers. In 1989, prior to this change in the CPS, prevalence rates between the 2 surveys were significantly different in 18% of the states surveyed, and in 1992/1993, after the change, prevalence rates were significantly different in 47% of the states surveyed. Not only do we need to be aware of these differences between and within studies, but we must also acknowledge that youth may have different perceptions than researchers do regarding operational definitions of key smoking terms. One qualitative study found that youths rarely consider themselves to be smokers, even if they smoke once a week.11 Researchers have suggested that we may need to examine the relationships between selflabels and behavioral measures and to study the issues from the perspectives of youths. 3,12 Because irregular smoking patterns make it difficult for youths to provide an account of their smoking status, Backinger and colleagues recomAm J Health Behav.™ ™ 2009;33(6):760-768

mend that a more accurate measure of youth smoking is needed, whereas others have also commented on the need to rethink the ways that youths’ smoking is assessed.4,13 Because youths may vary widely in their intensity (ie, how much and how often) or recency of smoking when perceiving themselves as smokers, it is important to assess the relationship between measures of youths’ tobacco use and youths’ perceptions.11,14 The purpose of this study was to explore different behavioral criteria (eg, smoking intensity and recency) that youths consider when determining their own smoking status. Youths’ perceptions of their smoking status were analyzed according to 3 different classifications: a 30-day classification (ie, having smoked in the past 30 days), a 100-lifetime classification (ie, having smoked 100 or more cigarettes in a lifetime), and a combined classification (ie, having smoked in the past 30 days and also having smoked 100 or more cigarettes in a lifetime). It was hypothesized that a sizable number of youths who have smoked in the past 30 days do not perceive themselves as current smokers and that the combined classification more accurately reflects youths’ perceptions regarding their smoking status than does the 30-day classification. METHOD Data used in this study were collected from a student survey that was administered to middle school and high school youths in the fourth and final wave of a larger longitudinal study. A populationbased sampling strategy was employed at schools. Based on the decision of the school administrator, either all students enrolled in the targeted grades or only students who lived in the participating community enrolled within the targeted grades were sampled. For all schools, students in grades 7 through 12 were sampled. After gaining IRB approval, written assent and active parental consent were obtained from participants. The survey was completed by students from 21 middle schools and 20 high schools in 24 Illinois towns. Of 31,846 students eligible to complete the survey, parental consent forms were obtained for 20,815 students (65%). A total of 16,758 (53%) eligible participants completed the survey, and 303 surveys were excluded due to a variety of reasons (eg, missing data on 1 or more of

761

Youth Smoking Status

the 3 variables being analyzed, inconsistent or invalid responding across survey items, the participant age of 18 or over, etc). Because participants who have never smoked would be expected to perceive themselves as nonsmokers and because the purpose of the study was to determine perceptions of smoking status of youths who smoke, the final sample included only those participants who reported having smoked ever in their lifetime. Those who reported having never smoked in their lifetime were excluded from this study, leaving a final sample of 5165 participants. Participants The sample comprised youths in grades 7 through 12, including 2630 (50.9%) females and 2397 (46.4%) males. Percent totals do not equal 100% due to missing information. Ages ranged from 11 to 17 (M=15.7, SD=1.5). Regarding ethnic status, 68.5% of the participants were white, 18.7% were Latino, 7.3% were African American, and the remaining 5.4% responded to ethnicity as Other/Unknown. At the town level, population size of the 24 towns ranged from 5000 to 75,000 (M=20,792, SD=17,671), and household incomes ranged from $30,000 to $133,000 (M=59708, SD=20880). Total populations and median household incomes have been rounded to protect community confidentiality. Measures Student survey. The student survey was developed by the Youth Tobacco Access Project, and contained 74 items adopted from other established measures of students’ attitudes and behavior toward tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Questions were modified from the Youth Risk Behavior and the Teenage Attitudes and Practices Survey, as well as surveys developed by Jason et al, Rigotti and colleagues, and Altman et al15-19 Students also reported whether they had ever used tobacco in their lifetime, the frequency and intensity of their use, and whether they were current cigarette smokers. Variables Perceived smoking status. Perceived smoking status served as the dependent variable and was determined according to responses given to the question “Are you currently a cigarette smoker?” This item

762

was chosen because it reflected a very straightforward self-perception of respondents and because available responses were not based on individual beliefs, but rather the presence or absence of smoking behaviors. Responses available for this question included 1 positive response: “Yes, I currently smoke cigarettes” and 4 negative responses: “No, I quit within the last 6 months,” “No, I quit more than 6 months ago,” “No, I have tried cigarettes once or twice but stopped,” and “No, I have never smoked cigarettes.” Responses to this question were dichotomized into 2 types; those who responded, “Yes, I currently smoke cigarettes” were considered to perceive themselves as current cigarette smokers, whereas all others were considered to perceive themselves as current nonsmokers. Past-30-day smokers. Whether youths had smoked in the 30 days preceding completion of the survey served as the first independent variable and was determined according to responses to the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Seven responses were offered to this question, ranging from “None” to “All 30 days.” Responses to this question were dichotomized into 2 types in order to reflect those who smoked on 1 or more of the 30 days preceding survey completion and those who reported not smoking during that time period. Lifetime cigarette use. Whether youths had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetimes served as the second independent variable and was determined according to responses to the question “About how many cigarettes have you smoked in your entire life?” Eight responses were offered to this question, ranging from “None” to “100 or more cigarettes.” Responses were dichotomized into 2 types, in order to reflect those who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetimes and those who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes. Procedure Because the purpose of this study was to explore different behavioral criteria that youth might consider when perceiving themselves to be current cigarette smokers, we selected 3 classifications to test. First, we tested the 30-day classification by selecting youths who reported having smoked on at least 1 of the 30 days

Bottom et al

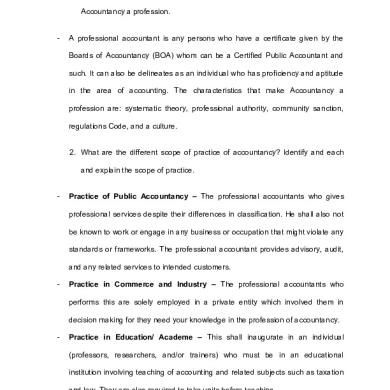

Figure 1 ROC Curves for 3 Tests

preceding completion of the survey and analyzed whether they perceived themselves to be current smokers. Then, we

tested the 100-lifetime classification by selecting those who reported having smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their

Table 1 Sensitivity and Specificity of the 30-Day Classification Smoked in the past 30 days? Yes No Smoker Perceived Smoking Status Nonsmoker

1260 True Positives

38 False Positives (Type I Errors)

1298 Total

1260 / 1298 = .97 Positive Predictive Value

639 False Negatives (Type II Error)

3228 True Negatives

3867 Total

3228 / 3867 = .83 Negative Predictive Value

1899 Total

3266 Total

5165

1260 / 1899 = .66 Sensitivity

3228 / 3266 = .99 Specificity

Am J Health Behav.™ ™ 2009;33(6):760-768

763

Youth Smoking Status

Table 2 Sensitivity and Specificity of the 100-Lifetime Classification Smoked 100+ Cigarettes Lifetime? Yes No Smoker Perceived Smoking Status Nonsmoker

870 True Positives

428 False Positives (Type I Errors)

1298 Total

870 / 1298 = .67 Positive Predictive Value

228 False Negatives (Type II Error)

3639 True Negatives

3867 Total

3639 / 3867 = .94 Negative Predictive Value

1098 Total

4067 Total

5165

870 / 1098 = .79 Sensitivity

3639 /4067 = .89 Specificity

lifetime and analyzed whether they perceived themselves to be current smokers. Finally, we tested the combined classification by selecting those who reported having smoked in the past 30 days and had also smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime. Again, we analyzed whether they perceived themselves to be current smokers. To determine which of the 3 classifications most accurately reflects youths’ perceptions of their smoking status, the sensitivity and specificity of each classification were analyzed. This 2x2 method of analysis was chosen because it provides simple, yet important, information regarding the perceptions and behaviors not only of youths who perceived themselves as smokers but also of those who perceived themselves as nonsmokers. In our study, sensitivity represents the level of agreement between youths who perceived themselves as current smokers and a classification that labels them as such, based on reported smoking behavior. Specificity represents the level of agreement between youths who perceived themselves as nonsmokers and a classification that labels them as nonsmokers, based on a reported lack of smoking behavior. RESULTS The 30-day classification yielded a sensitivity of .66 (Table 1). That is, two thirds

764

(66%) of youths who had smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days agreed with the classification and perceived themselves as current cigarette smokers whereas one third (34%) of youths who would be labeled as smokers, according to the classification, did not perceive themselves to be current smokers. For this classification, an ROC curve yields an area under the curve (AUC) of .83 (Figure 1), indicating that 30-day point prevalence correctly labels about two thirds of youths as smokers when they perceive themselves to be smokers and correctly labels almost all youths as nonsmokers when they perceive themselves to be nonsmokers. The 100-lifetime classification provided a sensitivity of .79 and a specificity of .89 (Table 2). The decline in specificity of the 100-lifetime classification is due to a high number (N=428) of false positives (Type I Errors). For these 428 cases, youths perceived themselves to be smokers, but would not be labeled as such according to the classification, which results in a low positive predictive value (PPV) of .67. An ROC curve for the 100-lifetime classification yields an AUC of .84 (Figure 1), which is only marginally better than the 30-day classification. The combined classification combined the criteria of both of the 2 previous tests, and yielded a sensitivity of .90 and a specificity of .90 (Table 3). As with the

Bottom et al

Table 3 Sensitivity and Specificity of the Combined Classification Smoked in the past 30 days and 100+ Cigarettes Lifetime Yes No Smoker Perceived Smoking Status Nonsmoker

862 True Positives

436 False Positives (Type I Errors)

1298 Total

862 / 1298 = .66 Positive Predictive Value

93 False Negatives (Type II Error)

3774 True Negatives

3867 Total

3774 / 3867 = .98 Negative Predictive Value

955 Total

4210 Total

5165

865 / 955 = .90 Sensitivity

3774 / 4210 = .90 Specificity

100-lifetime classification, this classification also demonstrates a high number of Type I Errors, resulting in a low PPV of .66. An ROC curve for this combined classification demonstrates an AUC of .90 (Figure 1), indicating that it does an excellent job of finding agreement regarding youths who perceive themselves as smokers as well as those who perceive themselves as nonsmokers. DISCUSSION As proposed by our first hypotheses, we found that a considerable number of youths who had smoked in the past 30 days did not perceive themselves as current cigarette smokers. When analyzing the common classification of 30-day point prevalence, the sensitivity is quite low as a result of 639 false negative cases in which youths had smoked in the past 30 days, yet did not consider themselves to be current cigarette smokers. In order to explain these discrepancies, we analyzed the 639 false negatives and found that 379 (59%) indicated having tried smoking once or twice but stopped. It is possible that these youths might have been experimenting with cigarettes and were in an early stage of smoking acquisition, and therefore had not smoked enough times to perceive themselves as current smokers. Another 174 (27%) of the false negatives responded that they had quit Am J Health Behav.™ ™ 2009;33(6):760-768

within the past 6 months. Although they reported having smoked in the past 30 days, it may be that these youths had attempted to quit within the past 6 months, but had slipped 1 or more times in the past 30 days. Having either stopped smoking for a considerable length of time or reduced their smoking a great degree, these youths may have perceived themselves as former rather than current smokers. Together, these 2 groups account for 86% of the false negatives found by the 30-day classification, and perhaps it can be expected that they perceived themselves as nonsmokers. However, reports of lifetime cigarette use among the 639 false negatives indicate that 418 (65%) had smoked at least 6 cigarettes in their lifetimes and 198 (31%) had smoked more than 25 cigarettes in their lifetimes. Considering their perceived status as nonsmokers, these youths may be at considerable risk for continued smoking, due to the frequency and recency of their smoking behaviors. Results from the 100-lifetime classification provide a sensitivity of .79, indicating that youths who meet this criterion are more likely to perceive themselves as current smokers than those who report smoking in the past 30 days. However, a closer analysis shows that 191 (84%) of the 228 false negative cases reported having quit smoking, and it is plausible

765

Youth Smoking Status

that a considerable number of them had abstained for more than 30 days. Specificity of this 100-lifetime classification is .89, indicating that compared to the 30day classification, there is less agreement between youths and the classification regarding nonsmoking status. Of the 428 false positive cases in which youths perceived themselves to be current smokers, but the classification does not label them as such, a great majority (93%) reported having smoked in the past 30 days. This group includes youths who reported having smoked recently but had not yet smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes. This classification provides a higher AUC than the 30-day classification does, but because it accounts only for total lifetime consumption, and not how recently youths have smoked, it may be ill-suited for determining smoking status. We found that youths are more likely to perceive themselves as current smokers if they have smoked in the past 30 days and have smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetimes, as the combined classification was the only 1 of the 3 to reach .90 for both sensitivity and specificity. This is important because sensitivity and specificity typically have an inverse relationship, in which one increases as the other decreases and vice versa. Thus, it is often difficult for both to reach .90 or higher. Despite the high levels of sensitivity and specificity of the classification, however, it produces a high number (N=436) of false positive cases and a low PPV of .66, which is affected by smoking prevalence rates. This means that 436 (36%) of the 1298 youths within the entire sample who perceived themselves as smokers did not meet the behavioral criteria of the combined classification. The implications of this low PPV may be important in the development and implementation of effective education and cessation programs. For example, if a program were designed to target youths who meet the specific behavioral criteria of this combined classification, it would exclude many youths who perceive themselves as smokers. Of the 3 classifications that we tested, the combined classification most accurately reflects both smoking recency and intensity as they relate to perceived smoking status and thereby demonstrates the highest AUC. However, this classifi-

766

cation may not be the most appropriate measure to use when assessing smoking status of youths for intervention purposes because many factors, behavioral or otherwise, can influence whether youths perceive themselves as current smokers. For this reason, we must be cautious as to how youths are approached regarding smoking issues. For example, de Vries et al found that gauging and responding to youths’ attitudes and beliefs regarding smoking issues led to increased acceptance of their new health education program. 14 Recently, several researchers have suggested the importance of studying issues of youths’ smoking from the perspective of the youths, and the present study provides evidence that there is indeed discordance between youths and researchers regarding behavioral criteria used to classify youths as smokers.4,11,20 Mermelstein and colleagues suggested that measuring smoking based on a single criterion is likely to provide insufficient information, whereas others have proposed using a 3-item measure (eg, lifetime use, past 30-day use, and current use) when monitoring smoking progression of youths as they enter young adulthood.3,8 One measurement, the Minnesota Smoking Index (MSI), measures youths’ smoking based on multiple items, including lifetime, past week, and past 24-hour use, and it is highly correlated with biochemical measures among adolescents.21,22 Although using such reported behavioral criteria may be sufficient for determining smoking rates among youths, our study indicates that such criteria do not always accurately capture youths’ perceptions of their smoking status. This study suggests that the most appropriate method of determining smoking status of youths may depend on the purpose of the study (eg, determining prevalence rates or developing effective educational programs). We propose that further research be conducted in order to more fully understand how smoking behaviors of youths and operational definitions regarding smoking status affect smoking prevalence rates, as well as youths’ perceptions of their own smoking status. Results from this study are subject to several limitations. First, a large percentage (35%) of students who were eligible to complete the student survey did not return parental consent forms in or-

Bottom et al

der to participate, and this self-selection may have excluded from the study many youths who are at greater risk for smoking.23 Second, our study relied heavily on self-reports of cigarette use, which have been found at times to be either overreported or underreported by youths, depending on a variety of social circumstances.3 Third, the survey question used to determine the dependent variable is based on self-perceptions, whereas the available responses to the question are based on reported behaviors that may have influenced some participants’ responses to the question. Finally, youths’ accountability of past recent smoking may be dependent on smoking intensity and/ or frequency, although it has been found that youths appear to report health-risk behaviors reliably over time.5,24 In summary, researchers typically classify youths as current smokers if they report having smoked in the past 30 days although not all youths who smoke share this belief. Although 30-day point prevalence may be the most accurate method of determining smoking prevalence rates among youths, prevalence rates are difficult to measure as youths enter into young adulthood because the operational definition of current smoker is different for youths than it is for young adults. Whether youths who smoke perceive themselves to be current smokers depends on a variety of factors, such as how recently they have smoked or how many cigarettes they have smoked in their lifetimes. Additionally, youths’ perceptions of their smoking status may impact the level of interest or cooperation that they maintain in regard to educational programs. In order for cessation and prevention programs to be most effective, we suggest that researchers continue to study smoking issues with an awareness of youths’ perceptions. Acknowledgments The authors appreciate the funding provided by the National Cancer Institute (grant number CA80288). We also thank Nicole Porter, PhD; David Mueller, PhD; and Diana D. Anderson, BA, at DePaul University for their insight and editorial efforts. REFERENCES 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Midcourse Re-

Am J Health Behav.™ ™ 2009;33(6):760-768

view—Tobacco Use (online). Available at: http:/ /www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed March 22, 2008. 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(SS-1):1157-1161. 3.Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, et al. Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:395403. 4.Backinger CL, McDonald P, Ossip-Klein DJ, et al. Improving the future of youth smoking cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl 2):S170-S184. 5.Eppel A, O’Laughlin J, Paradis G, et al. Reliability of self-reports of cigarette use in novice smokers. Addict Behav. 2006;31:17001704. 6.Colder C, Balanda K, Mayhew K, et al. Identifying trajectories of adolescent smoking: an application of latent growth mixture modeling. Health Psychol. 2001;20(2)127-135. 7.Milton M, Maule C, Backinger C, et al. Recommendations and guidance for practice in youth tobacco cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl 2):S159-S169. 8.Delnevo CD, Lewis MJ, Kaufman I, et al. Defining cigarette smoking status in young adults: a comparison of adolescent vs. adult measures. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28(4):374380. 9.MacPherson L, Myers MG, Johnson M. Adolescent definitions of change in smoking behavior: an investigation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(5):683-687. 10.Arday DR, Tomar SL, Nelson DE, et al. State smoking prevalence estimates: a comparison of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and Current Population Surveys. Am J Public Health. 1997; 87(10):1665-1669. 11.Baillie L, Lovato CY, Johnson JL, et al. Smoking decisions from a teen perspective: a narrative study. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(2):99-106. 12.Treacy M, Hyde A, Boland J, et al. Children talking: emerging perspectives and experiences of cigarette smoking. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(2):238-249. 13.Evans NJ, Gilpin E, Pierce JP, et al. Occasional smoking among adults: evidence from the California Tobacco Survey. Tob Control. 1992;1:169-176. 14.de Vries H, Weijts W, Dijkstra M, et al. The utilization of qualitative and quantitative data for health education program planning, implementation, and evaluation: a spiral approach. Health Educ Behav. 1992;19(1):101-115. 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(12):1-13. 16.Allen K, Moss A, Giovino G, et al. Teenage tobacco use: data estimates from the teenage

767

Youth Smoking Status

attitudes and practices survey, United States, 1989. Adv Data. 1993;224:1-20. 17.Jason LA, Berk M, Schnopp-Wyatt DL, Talbot B. Effects of enforcement of youth access laws on smoking prevalence. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(2):143-160. 18.Rigotti NA, DiFranza JR, Chang Y, et al. The effect of enforcing tobacco-sales laws on adolescents’ access to tobacco on and smoking behavior. N Eng J Med. 1997;337:1044-1051. 19.Altman DG, Wheelis AY, McFarlane M, et al. The relationship between tobacco access and use among adolescents: a four community study. So Sci Med. 1999;48:759-775. 20.Nichter M, Nichter M, Thompson PJ, et al. Using qualitative research to inform survey development on nicotine dependence among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend.

768

2002;68:S41-S56. 21.Pechacek TF, Muray DM, Luepker RV, et al. Measurement of adolescent smoking behavior: rationale and methods. J Behav Med. 1984;7(1):123-140. 22.Murray DM, Prokhorov AV, Harty KC. Effects of a statewide antismoking campaign on mass media messages and smoking beliefs. Prev Med. 1994;23:54-60. 23.Rothman KJ, Greenland, S. Precision and validity in epidemiologic studies. In Rothman, KJ & Greenland, S (Eds). Modern Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 1998:115-134. 24.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:336-342.