Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Safety Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/safety

Challenges influencing the safety of migrant workers in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Italy, Spain, and the UK ´ b, d, * Rose Shepherd a, Laura Lorente b, Michela Vignoli c, Karina Nielsen a, Jos´e María Peiro a

Institute of Work Psychology, Sheffield University Management School, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 1FL, UK IDOCAL Research Institute, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain c Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy d Ivie, Valencian Institute of Economic Research, Valencia, Spain b

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Keywords: Safety Construction Migrant Workers Training Qualitative Research

The construction industry is notoriously high risk for accidents, injuries, and deaths, particularly for non-national or migrant workers, who comprise a significant proportion of the workforce. This paper presents an interna tional, qualitative study focused on exploring the challenges which influence the safety of migrant construction workers in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, we formulated two research questions about the challenges relating to safety that migrant workers face and the challenges to safety training effectively improving migrant workers’ safety behaviours. We present our template analysis of semistructured interviews and focus groups with 88 participants from four occupational groups across all three countries. This identified commonalities and differences in interpretations of the primary challenges to migrant workers’ safety, amongst participants from the various occupational groups (workers, site supervisors, safety trainers and safety experts) in Italy, Spain, and the UK. These were associated with: increased use of sub contractors; dilution of safety standards down the supply chain; pressure to breach safety regulations on site; differing safety-related attitudes and behaviours due to national cultural differences, language barriers and issues relating to training (provision, delivery, language, content and transfer). Finally, we summarise the contributions and limitations of our study, arguing further interventions related to safety training are needed, along with ethnographic studies to explore how both macro-level and contextual factors affect safety outcomes for migrant construction workers.

1. Introduction

According to the Centre for Corporate Accountability, in 2007/2008, 17% of deaths in the UK construction industry were migrant workers, despite accounting for only 8% of the workforce at that time (CCA, 2009). Similarly, in 2018, migrant workers accounted for 13% of the 115 fatal injuries on Italian construction sites (Istituto Nazionale Assi curazione Infortuni sul Lavoro, 2019) and 16% of the 113 fatalities on Spanish construction sites (Ministerio Trabajo y Economía Social, 2020). Despite these high rates, there has been little research carried focusing on migrant workers’ safety in European countries. The present study focuses on the challenges and opportunities migrant workers in the construction industry face and the challenges and opportunities for preventing accidents and injuries among this group of workers, e.g.,

The construction industry, which provides employment for around 220 million people across the globe (International Labour Organization, ILO, 2019), has a particularly poor record in terms of safety (Buckley, Zendel, Biggar, Frederiksen, & Wells, 2016). Non-national or migrant workers1, who comprise a significant proportion of the construction workforce worldwide, are at significantly increased risk of death and injury in comparison with their native-born counterparts (Eurostat, 2011, 2019; Giraudo, Bena, & Costa, 2017; Guldenmund, Cleal, & Mearns, 2013; Hargreaves et al., 2019; Oswald, Sherratt, Smith, & Hallowell, 2017).

* Corresponding author at: IDOCAL Research Institute, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain. E-mail addresses:

[email protected] (R. Shepherd),

[email protected] (L. Lorente),

[email protected] (M. Vignoli), k.m.nielsen@ sheffield.ac.uk (K. Nielsen),

[email protected] (J.M. Peir´ o). 1 For this paper, we follow the United Nations’s (1990) definition of a migrant worker; “a person who is to be engaged, is engaged or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a State of which he or she is not a national”. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105388 Received 21 July 2020; Received in revised form 1 May 2021; Accepted 14 June 2021 Available online 23 June 2021 0925-7535/© 2021 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

an

open

access

article

under

the

CC

BY-NC-ND

license

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

through training migrant workers in safety. The contributions of our study are threefold. First, the majority of studies on construction safety have adopted a positivist approach (Oswald, Ahiaga-Dagbui, Sherratt, & Smith, 2020; Zou, Sunindijo, & Dainty, 2014) and Phelps and Horman (2010, p. 58) called for research that enhances our “understanding of the complex interactions that lead to many of the industry’s pervasive social and technical problems.” (2010, p.58), i.e., qualitative research is needed (Oswald, Sherratt, Smith, & Dainty, 2018; Zou et al., 2014) especially when the focus is on the direct and root causes of accidents (Park, Kim, Han, & Hyun, 2020). We used sensemaking theory (Weick, 1995) as our underpinning framework. Central to sensemaking theory is the assumption that sensemaking is a process through which people give meaning to their experiences. As key stakeholders, be it trainers, occupational health practitioners, supervi sors, native and migrant workers observe discrepancies between how native and migrant workers enact safety behaviours differently in the workplace with resulting near-miss accidents, injuries and accidents and react differently to safety training, either directly in the setting or through representation of safety statistics, they attribute meaning to these cues and try to explain, comprehend and understand why these differences occur (Weick, 1995) - and potentially also how these dif ferences could averted. In the present study, we used focus groups and interviews to explore the sensemaking of our participants. Second, the majority of research on migrant construction workers’ safety has been conducted in the US with Hispanic and Latino workers (e.g., Hallowell & Yugar-Arias, 2016; Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010), in Hong Kong and China (e.g., Chan, Javed, Lyu, Hon, & Wong, 2016; Lyu, Hon, Chan, Wong, & Javed, 2018; Man, Chan, & Wong, 2017), and in Australia (e.g., Lingard, Hallowell, Salas, & Pirzadeh, 2017; Loosemore & Malouf, 2019; Trajkovski & Loosemore, 2006). There are compara tively few studies in European countries and these have failed to consider multiple perspectives on migrant workers safety. The majority of studies on migrant workers’ safety in construction employ a simple perspective approach, focusing on either native workers in the UK (Briscoe, Dainty, & Millet., 2000), migrant workers in the UK (Dainty, Gibb, Bust & Goodier, 2007; Hare, Cameron, Real, & Maloney, 2013), objective accident data in Spain (Lopez-Jacob et al., 2010; Ronda-Perez et al., 2019) and Italy (Mastrangelo et al., 2010). Only three studies included multiple key stakeholder perspectives. Oswald, Wade, Sherratt and Smith (2019) explored site supervisors’ and health and safety ex perts’ perspectives on safety communication in an ethnographic study in the UK. Oswald et al. (2020) explored migrant workers in an ethno graphic study involving all working in the construction site. Finally, Tutt, Dainty, Gibb, and Pink (2011) employed an ethnographic approach to understand migrant workers and their manager’s perspec tives on safety in a UK construction site. There is thus a significant gap in the literature to identify what the key challenges and opportunities migrant workers face in three European countries, namely Italy, Spain and the UK. These countries are especially relevant to study these issues as they are included among the first five in the statistics about the annual production value of the construction industry in European countries2 in statistics of the recent years. Furthermore, migrant workers’ safety is not only dependent on migrant workers’ sensemaking of key challenges and opportunities but other key stakeholders play an important role in ensuring a safe climate in the construction site. In recognition of the multi-stakeholder perspective, we interviewed not only migrant workers but also their native colleagues, their supervisors, safety experts and safety trainers, all of whom have experiences with promoting migrant worker safety in the construction site. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use these approaches in these three countries, obtaining information from a larger group of stakeholders from multiple construction sites.

Third, safety training is crucial to ensure safety in the construction site (Guo, Li, Chan, & Skitmore, 2012). Training workers in safety be haviours is important as up to 80% of accidents in the workplace can be ascribed to workers’ behaviours (HSE, 2002) and workers report safety training to be the most important factor in making workplaces safer (Dingsdag, Biggs & Sheahan., 2008). A recent systematic literature re ´, Nielsen, Latorre, Shepherd, and Vignoli (2020) found view by Peiro only 18 papers published since 2000, which focused on safety training interventions for migrant construction workers, none of which were ´ et al. (2020) concluded that conducted in Europe. Furthermore, Peiro current state-of-the art of safety training of migrant workers in the construction industry fails to deliver on its promises. In the present study, we take a step back and explore the factors that key stakeholders perceive to be important for training of migrant workers in the con struction site to be effective. 1.1. Challenges to ensuring the safety of migrant construction workers Being a migrant worker in a high-risk sector such as the construction one needs to take into consideration that also social, political and eco nomic aspects can play an important role on the safety conditions and safety outcomes. The existing literature on migrant workers in con struction, predominantly conducted in the US have identified key challenges faced by migrant workers, these include poor working con ditions, cultural differences, the role of language and the lack of access to safety training. 1.1.1. Poor working conditions of migrant workers The global increase in outsourcing within the industry over the past 30 years has resulted in long supply chains of subcontractors, with re sponsibility for health and safety being devolved downwards (Buckley et al. 2016). Moreover, work is commonly farmed out to small con struction companies employing foreign workers (Fellini, Ferro, & Fullin, 2007; Oswald et al., 2020). Migrant workers often enter the labour market at the lowest possible point, increasingly their vulnerability to exploitation, which can severely compromise their safety on site (Fellini et al., 2007; Oswald et al., 2020). Migrant workers often take on construction work because jobs are not available in their preferred field (Buckley et al., 2016; Pollard, Latorre, & Sriskandarajah, 2008), accept lower levels of pay than na tional colleagues (Dainty et al., 2007; Fellini et al., 2007) and even tolerate wage theft (Fussell, 2011). Migrant workers are less likely to complain about unsafe working conditions for fear of dismissal or repatriation (Lopez-Jacob et al., 2010), and often fail to report injuries, for fear of reprisal and not being able to afford time off work (Mas trangelo et al., 2010). Migrant workers also come under increased pressure to cut corners and work quickly, and are often given riskier, more dangerous tasks on site compared with native workers (Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010; Williams, Ochsner, Marshall, Kimmel, & Martino, 2010). Results presented clearly show that working conditions are different between native and migrant workers and these differences can have an impact on workers’ safety, however, the extent to which these conditions translate to the European context remains unclear. 1.1.2. Influence of cultural aspects on migrant worker safety Studies have explored the impact of national cultural characteristics on migrant workers’ safety-related values, attitudes, and behaviours (Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010; Oswald et al., 2017). Attitudes towards safety have been found to differ between migrant and non-migrant workers. Studies have found Hispanic construction workers in the US (Welton et al., 2018) and migrant workers in Hong Kong, primarily from Pakistan and Nepal (Chan, Javed, Wong, Hon, & Lyu, 2017), perceive safety to be less important than native workers. Furthermore, in Latino cultures a “machismo” attitude has been found to have a negative impact on safety performance (Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010, p.184). Hofstede’s (1980, 2001) cultural dimensions of power distance,

2 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/964804/construction-industry-pro duction-value-by-country/)

2

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

individualism-collectivism, and masculinity-femininity, have also been drawn upon to explain differences in safety behaviours. In line with the tendency for Latin American cultures to have high power distance re lationships (i.e., a more hierarchical society), foreign-born Hispanic workers are less likely to challenge perceived authority, and more likely to accept unsafe tasks and working conditions, such as lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) (Robertson, Kerr, Garcia, & Halterman, 2007). In addition, studies have found migrant construction workers in the UK (Oswald et al., 2017) show lower levels of safety awareness when power distance between themselves and management is greater. The collectivist, family-oriented nature of Latin American cultures also appears influential. Menzel and Gutierrez (2010) describe how Latino workers in the US were motivated to behave safely on site in order to ensure they returned home to their families. Conversely, Hal lowell and Yugar-Arias (2016) found stronger, more extensive family ties among Hispanic workers increased the likelihood of family-related issues being a distraction at work, reducing safety awareness on site. It is clear that culture plays a key role in workers’ safety as migrant workers can have different safety values and beliefs.

been noted. First and foremost, is the apparent lack of training available, particularly at lower levels of the subcontracting supply chain, where the majority of workers are self-employed (Briscoe, et al., 2000; Chan, Clarke, & Dainty, 2010). When training is received, migrant workers’ language skills frequently hamper their learning, reducing training effectiveness (De Souza et al., 2012; Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010). Stra tegies proposed to overcome these language barriers include training in migrant workers’ mother tongue (Dainty, Gibb, Bust & Goodier, 2007), Dainty, Green & Bagilhole, 2007; Loosemore & Chau, 2002). An unin tended consequence of training workers in their first language is they may fail to develop their secondary language skills, impacting their safety on site (Trajkovski & Loosemore, 2006; Oswald et al., 2015) and address the challenges of different cultural values (Brunette, 2005). In addition, as outlined above, interpretation of signs and audio-visual materials also appears to differ between migrant groups (Bust et al., 2008; Hare et al., 2013). In relation to training content, interventions appear to focus pre dominantly on legislation and technical safety skills, such as electrical safety and falls from height (Forst et al., 2013; Menzel & Shrestha, 2012). Few studies include nontechnical or ‘soft’ skills, such as hazard awareness and cross-cultural communication (e.g., Harrington, Materna, Vannoy, & Sholz, 2009; Jaselskis et al., 2008). Yet, as Vignoli et al. (2021) argue, nontechnical skills such as communicating about safety hazards, working as a team to foster a sense of collective safety, and being aware of hazardous situations, are vital for migrant worker safety. Only one study has explored what happens once migrant workers return to the construction site, i.e. whether trained migrant workers transfer skills and knowledge acquired through training (Hussain, Pedro, Lee, Pham, & Park, 2020). Along with a lack of information about effective safety training for migrant workers, the literature presented is mainly based on a migrant workers’ perspective. This is important as migrant workers are the target of safety training, however, other key stakeholders in the construction sector play important roles in influencing safety training content and delivery, such as safety experts and safety trainers. Moreover, the views of supervisors and native colleagues are also relevant to consider how learning is used in the construction site and whether transfer occurs. The view of all these actors which play important roles such as effectively teaching training skills, promoting safety behaviours, and influencing safety climate are underreported highlighting an important gap in the literature that needs to be filled. Weick (1995) argued that sensemaking occurs in situations where success measures are lacking. Together the challenges faced by migrant workers in accessing good quality safety training calls for a step back to explore the sensemaking of key stakeholders relating to safety training of migrant workers to understand the key meanings they attribute to the challenges and opportunities key stakeholders perceive in relation to safety training of migrant workers in construction in the context of Italy, Spain and the UK. We therefore formulated our second research question:

1.1.3. Language barriers for migrant workers Given the heterogeneity of construction workers on site, it is un surprising that language barriers have a detrimental impact on safety (Bust, Gibb, & Pink, 2008; Tutt, Dainty, Gibb, & Pink, 2011). Workers are often required to collaborate closely and to react quickly to verbal instructions from their co-workers, as they navigate the fast-paced, hazardous construction environment (e.g., Dainty et al., 2007; Gulden mund et al., 2013). Even for migrant workers with proficient language skills, effective communication is hampered by local accents and di alects, the use of jargon, and different technical construction-related terms being used in different countries (Oswald et al., 2019). A further challenge is that migrants typically work in close-knit teams with family members and friends and thus, often have a poor command of the native language (Al-Bayati, Abudayyeh, Fredericks, & Butt, 2017). To circumvent these language barriers, body movements and hand gestures are frequently used to communicate messages to migrant workers (Oswald, Smith, & Sherratt, 2015; Wu, Luo, Wang, Wang, & Sapkota, 2020). Additionally, construction site supervisors often rely on one member of the migrant group to translate the information for his or her co-workers (e.g., Bust et al., 2008; Guldenmund et al., 2013), however, means of checking whether communications have been conveyed and understood correctly are limited (Oswald et al., 2019; Tutt et al., 2011). In one study conducted in the European context, Hare et al. (2013) found that workers born outside Europe (from Africa and India) were less likely to correctly identify common warning signs compared to their co-workers born inside Europe. Language is therefore a crucial aspect that needs to be taken into consideration when addressing migrant workers’ safety also in terms of safety training. In summary, these three key challenges to migrant worker safety in the construction industry call for further research on whether these are perceived in Italy, Spain and the UK, but also calls for exploring whether there may be factors which may be used to promote migrant worker safety. We therefore asked our first research question:

Research Question 2: What key challenges and opportunities con cerning migrant workers’ safety training exist in the construction sector in Italy, Spain and the UK?

Research Question 1: What are the key challenges and opportunities migrant workers face relating to safety in the construction sector in Italy, Spain and the UK?

2. Material and methods This paper draws on data from a three-year project funded by the Erasmus + programme of the European Union (grant number 2017–1UK01-KA202-036560), with partners across Italy, Spain, and the UK. In this section, we outline our research approach, including how we collected and analysed our data.

1.2. Safety training as a way to overcome migrant workers’ challenges in safety Safety training is a key mechanism for enhancing safety climate and performance for migrant construction workers, thereby reducing acci dents and injuries (Cunningham et al., 2018). Notwithstanding the limited body of research identified by Peir´ o et al. (2020), several problems with safety training for migrant construction workers have

2.1. Research approach Based on sensemaking theory (Weick, 1995) we explored how safety 3

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

experts, safety trainers, supervisors, native and migrant workers make sense of their construction environment and construct their social re alities in this context (Gephart, 2013). Rather than seeking to access an objective, unbiased ‘truth’ about safety in construction, particularly for migrant workers, we were interested in uncovering our participants’ subjective experiences (Gephart, 2018). We wanted to explore their attitudes, values, and beliefs in relation to safety in the construction industry. We wanted to learn about their realities of safety on the con struction site and the meanings they attached to different situations (Schutz, 1973) and how they made sense of the differences in safety in the construction site and the differential reactions to training of migrant workers. Thus, we employed a qualitative methodology, collecting our data via semi-structured interviews and focus groups, as detailed below.

17 experts participated in three focus groups (one per country), as did all 21 trainers (one focus group per country). We selected different strategies depending on the group of in formants we obtained information from. The workers were interviewed individually, while the rest of the participants took part in focus groups. Researchers from the three countries jointly designed the interview guide based on the objectives of the study and the previous theoretical review. We considered semi-structured interviews to be suitable for gathering information from workers for several reasons: confidentiality could be guaranteed and the adaptation to the language constraints and requirements was easier when individual interviews were undertaken. We considered focus groups to be appropriate for the remaining, three groups, supervisors, safety trainers and safety experts, as exchange of views and debate were important aspects of the data gathering to enhance its richness and value. Interviews and focus groups lasted be tween 25 min and 2 h, and were audio-recorded, with permission, to aid transcription and enable the interviewer to engage fully with the par ticipants. Each session began with background information (e.g., na tionality, length of time in host country, experience in construction industry), to set the information in context and help put the participants at ease, followed by topic-related questions informed by the existing literature. These questions related to: attitudes towards safety on the construction site; risks typically faced by migrant construction workers; safety behaviours commonly performed and observed on site; and ex periences with safety training. Some example questions that were used in the interviews are “Do you think your company could do something to help workers who have language problems?” and “How does your su pervisor ensure that there is a good communication between col leagues?”; and examples questions in the focus groups are “Could you point out good practices in terms of safety that are usually found on a daily basis on construction sites?” and “How do you think training could be improved to overcome the barriers that language can pose?”. Ques tions were open-ended and their ordering varied according to partici pants’ responses. Issues deemed of relevance to the research were probed further, thereby enabling an in-depth exploration of partici pants’ individual perceptions and experiences. On completion, all in terviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim, in the host country’s language and, following analysis, key findings were translated into English.

2.2. Participants A purposive sampling technique, which involves seeking out “groups, settings and individuals where […] the process being studied is most likely to occur” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000, p.370), was used to recruit and select participants who would provide a rich picture of safety in the con struction industry from a range of perspectives. A total of 88 participants from four occupational groups across Italy, Spain, and the UK took part in the study: workers (national and migrant), supervisors, safety experts and safety trainers. Migrant and national workers were interviewed individually, whereas site supervisors (i.e. construction workers with safety responsibilities), experts (i.e. professionals with experience related to safety such as occupational risk prevention technicians, mutual insurance companies…), and trainers (i.e. professionals dedi cated to teach courses on occupational risk prevention in the construc tion sector), participated in focus groups (see the distribution per country and roles in table 1). The 88 participants ranged in age between 19 and 64, with the majority being over 40. Only one participant (a migrant worker based in the UK) was female. Three quarters (66 people) were from the host country originally (i.e., either Italy, Spain, or the UK), whilst one quarter (22 people; 19 migrant workers and three supervisors in the UK) were migrant workers, originating from Albania, Bulgaria, Ecuador, Estonia, India, Ireland, Kosovo, Latvia, Moldova, Morocco, Portugal, Romania, Tunisia and Turkey. The migrant workers had been in their host coun tries for between 3 and 35 years, with the majority being resident for at least 10 years. They had worked in the construction industry for be tween 2 and 27 years, and undertook numerous different roles including production operatives, ground workers, painters, steel workers, concrete finishers, joiners, and carpenters.

2.4. Data analysis In all three countries we used a template analysis to analyse the in terviews and focus group transcripts. This type of analysis allows for both inductive and deductive approaches (King, 2004). The existing literature on safety practices among migrant workers in the construction sector and in particular the training they receive provided the back ground for our research questions. To explore the specific sensemaking of our informants in their respective contexts, we employed an openended approach to identify the challenges faced by migrant workers and their training provision. We analysed and coded interview tran scripts in three stages. In the first stage, the first author familiarised themselves with the data reading and re-reading the transcripts to identify “thought units” (Gioia & Sims, 1986). Thought units vary from one sentence to several sentences and capture a complete thought or idea relevant to the challenges or training of migrant workers in relation to safety. We identified the thought units within three overall themes based on our literature review on migrant workers’s conditions relating to our first research question: Working conditions, cultural aspects, language barriers and thought units relating to our second research question about safety training. We next analysed these systematically to identify concepts from the transcripts (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Concepts emerged from reading, re-reading and interpreting the thought units. In the second step of analysis, we categorised statements related to similar categories into concepts and assigned these descriptive labels (codes) (Miles &

2.3. Data collection Data were collected across Italy, Spain, and the UK between March and September 2018, via 34 semi-structured interviews and eight focus groups. These methods were chosen for their flexible nature, allowing the same topics to be addressed with all participants while also enabling probing of arising areas of interest (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2019). All 30 construction workers participated in individual interviews, as did the four supervisors from the UK. The remaining 16 supervisors from Italy and Spain took part in focus groups (one per country). Similarly, all Table 1 Description of sample data. Group

Italy

Spain

UK

N

%

Non-national workers National workers Site supervisors Safety experts Safety trainers Total

6 4 9 5 8 32

7 3 7 6 6 29

6 4 4 6 7 27

19 11 20 17 21 88

22% 12% 23% 19% 24% 100%

4

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Huberman, 1994). We continued categorisation until saturation was reached and we had assigned relevant thought units to a concept (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). We identified 23 concepts (challenges and opportu nities in relation to migrant workers’ safety and safety training of migrant workers in the construction industry). In the third stage, we classified concepts into ten overarching themes, capturing the challenges and opportunities faced by migrant workers within the four key challenges identified with the literature review (i.e., working conditions, cultural aspects, language barriers and safety training). Specifically, relating to the first research question, we identified an additional theme of opportunities for promoting migrant worker safety, and regarding to the second research question about migrant worker safety training, we found this could be divided into five themes: Provision of training, training language, training delivery, training content and training transfer. Tables 2 and 3 provide a summary of our analysis and in the results section the overarching themes are explained. To aid the analysis process NVIVO software (QSR International) was utilised. Each national team, using the same codebook but in their respective language, analysed the data from their own country, and this was then translated into English. The codebook was designed based on the ten overarching themes previously identified (which in turn were divided into sub-themes): migrant workers who they are, what do they do, risks they face, safety training for migrant workers, training in the work context, training evaluation, training supervisors, safety outcomes, safety norms and learning from accidents and certifications and related functions. Each of the transcripts was split into 15-minute segments and then 20% of these 15-minute segments was randomly selected to be coded by a second researcher to assure inter-rater reliability.

Table 2 Challenges and opportunities relating to migrant workers’ safety in construction. Overarching themes

Concepts

Representative quotes (Thought units)

Country

Subcontractors’ use of migrant workers

Cheap labour

Plasterers working for 2 or 3 Euros per hour. This is because they are the subcontract of the subcontract of the subcontract” (Italy, Supervisor) I think that in general, migrant workers are not qualified. They are a cheap workforce, to simply cover areas of work that are needed here (Spain, Trainer) Working without being paid from the organization. This set me back 70,000 Euros (Italy, Migrant worker) In small companies is where we have more problems, as the majority of the time, safety plans do not work” (Spain, Safety expert) From what we see every day, migrant workers usually do lowly hand jobs, usually cargo handlings, porterage, that’s all (Italy, Supervisor) Speed is more rewarded than the quality of the work or fulfilling safety norms. (Spain, Migrant worker) You can do things the safe way which is slower, or you can do things the fast way. So things like heights and stepladders; somebody could climb onto the forklift bars and be raised up that way instead and then they are risking falling and going down, so sometimes when the safe way takes a long time, we do things to cut corners to make it quicker. (UK, Migrant worker) There is diversity. There are people who come from countries where the preventive culture is practically invalid and they are very reckless. For them, working with risks seems to be almost always the norm (Spain, Supervisor) If they [migrant workers] don’t know culturally what level of health and safety to expect on site […] they will just do what they are being asked to do and that may not be good practice” (Supervisor) In some ethnic groups there is an underlying

All countries

Lack of previous experience in industry

Wage theft

Dilution of safety standards

Discriminatory allocation of riskier work

Supervisors allocating “dirty” jobs

3. Results Pressure to breach safety regulations

Our analysis revealed important findings of migrant workers’ con ditions in the construction industry and the training initiatives to pro mote safety behaviours. Importantly, our results confirm previous research, however, also point to novel insights of migrant workers’ safety in the construction industry in Italy, Spain and the UK. 3.1. Migrant workers’ safety opportunities and challenges In response to our first research question, we also identified the same challenges as in the literature but also identified an additional challenge focused on the top opportunities for promoting safety behaviours among migrant workers. 3.1.1. Subcontractors’ use of migrant workers Consistent with existing literature (e.g., Buckley et al. 2016; Dainty & Chan, 2011; Fellini et al., 2007), participants from all three countries discussed how the fragmented structure of the construction industry, with its increasing reliance on migrant workers and subcontracting re lationships, impacted safety in a number of ways. Participants reported smaller subcontractors recruiting primarily migrant workers, despite them having little or no prior construction experience and poor language skills, because they are “cheap labour” (Supervisor, UK). Echoing these sentiments, a site supervisor from Italy noted “plasterers working for 2 or 3 Euros per hour. This is because they are the subcontract of the subcontract of the subcontract”. Indeed, in line with research which suggests migrants often accept construction work because jobs are not available in their preferred discipline (Buckley et al., 2016; Pollard et al., 2008), only 6 of the 19 migrant workers (32%) in our sample had prior experience of con struction before moving to Italy, Spain, or the UK. The other workers had held a variety of jobs in their native countries, including farmer, factory worker, turbine worker, subway workman, fisherman, window fitter, and sales assistant. A trainer in Spain commented, “I think that in general, migrant workers are not qualified. They are a cheap workforce, to simply

Cultural aspects

Diversity

Lack of awareness of host country values

Machismo

All countries

All countries

All countries

All countries

All countries

All countries

All countries

All countries

(continued on next page)

5

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Table 2 (continued ) Overarching themes

Concepts

Demands on supervisors

Language barriers

Opportunities for promoting safety at work

Repercussions of difficulties with language

Role-modelling

Use of soft skills

Representative quotes (Thought units) machismo, which tends to underestimate some dangers. They think, ‘I am a grown man and I do not wear the helmet’. Mainly migrant workers from the East European Countries report a little bit of carelessness due to the fact that they are rough and tough guys (Italy, Supervisor) Supervisors must speak two languages: the language of the office and the language of the people of the street […] with immigrants the key aspects are respect and tolerance, and empathy with the rest of the workers (Spain, Supervisor) What usually happens is that the migrant worker with the better host language tends to become the group leader and usually translates instructions from supervisor to workers in the group who are from the same country of origin (Spain, supervisor). We try to help those who have problems by translating and telling them how to do things in the site, even with signs (Spain, Native worker) People usually tend to work in groups composed by other people who share the same language (Spain, Safety expert) If no one wears a helmet, they [migrant workers] also do not use it; if their bosses do wrong manoeuvres, they imitate (Italy, Supervisor) So, if somebody spots a hazard, you go to a supervisor or manager and say: ‘right this needs to be resolved, how can we resolve it?’ and you both talk to each other and decide it this way, or that way, or whatever and to me communication is the biggest safety feature of all, because if things aren’t communicated properly the job doesn’t get done. (UK, Native worker)

Table 3 Specific challenges and opportunities relating to safety training of migrant workers in construction.

Country

Overarching themes

Concepts

Representative quotes (Thought units)

Country

Provision of training

Lack of investment among self-employed and microbusinesses

Well, I want you to work, but as you’re self-employed you can pay for that course yourself […] if you don’t, bye, bye (UK, Safety expert) I have been waiting for electric pallet training for three years, it is cheap to do, at first everybody could use it but now only two people can use it. People have had the training, so I’ve been waiting three years for the training for that. I think that is really stupid because it slows you down on your jobs. So you can still use it without training but it’s not good health and safety behaviour. (UK, Migrant worker) “You only need to look at the differences between the migrant workers and the native workers, so that’s your solutions, govern, those differences to bring them at the same level as native workers. Otherwise, there will be a conflict because you’re treating them more or you, you will be seen to care about them a lot more than native workers. So by inventing training schemes, you’re separating people. Of course, because you’re differentiating people. You don’t want to do that because you causing division in the construction industry. Ah, yeah. But we’re better than you so we have to go train him every three months free of charge and we get paid for it, whereas you have to work, you know what I mean? And it will cause a conflict.” (UK, Safety expert) Several of the trainees gave me a blank test sheet […] and then they told me ‘I do not know what is written here, it is not useful that I randomly answer the questions (Italy, Trainer) “You know it was a bit difficult to understand because before I didn’t know what was PPE. I have seen lots of times in some papers PPE and I’m thinking what is this? It is not easy a lot of this.” (UK, Migrant worker) “So on inductions, we will induct everybody onto our site, and we’ll induct them in English, and then we will

Spain, UK

Lack of training offered All countries

All countries Equal opportunities

All countries

All countries

Training language

cover areas of work that are needed here”. Furthermore, the literature reports migrant workers are willing to accept lower levels of pay than national workers (Dainty et al., 2007a) and even tolerate wage theft (Fussell, 2011). One migrant worker from Italy reported working “without being paid from the organization. This set me back 70,000 Euros”, describing not only how he did not receive his wages, but also how he had to cover the costs of materials and

Material available in native language only

Reliance on trainee translators

Spain, UK

Spain, UK

All countries

All countries

(continued on next page)

6

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Table 3 (continued ) Overarching themes

Concepts

Shared language

Training delivery

On-site training

Reasoning

Table 3 (continued ) Representative quotes (Thought units) expect the translator to then translate what we’ve spoken to those individuals. That induction can last, what, half an hour I’d say? Is he passing that information across? He’s probably passing 10 min of that half an hour induction across to that individual. So even on the basics of inducting that individual onto site, and getting him aware of what our site constraints are, our site issues, our site risks, etc. Are we properly passing it over to him? Probably not.” (UK, Trainer) “In a training environment there is always a difficulty that have they actually understood what it is that your, message that you’re trying to get across. Occasionally you’ll see people translating on behalf of others. Um, and again, that’s not ideal because you don’t know if they’re actually just maybe giving them the answer without them understanding what the question is or what the topic is about. Um, and you also don’t know whether they are translating in a way that it’s intended. “ Safety expert “We do not have problems with language because many times the mother tongue of migrant workers is Spanish, and if they come from other countries (for example from Africa), they already know some Spanish.” (Spain, Native workers) “In situ (on the construction site), they [migrant workers] see the risks better” (Spain, Supervisor) “It’s just that on site you learn things better than in the classroom.” (Spain, Native worker) “Honestly, I don’t know, maybe go on the site with us, show us problems make a connection between what you told us on the training and what we can see on the site and make a connection. I think that will increase our understanding again when I put it into work.” (UK, Migrant worker) “When things have been explained to me from a theoretical point of view, I started to understand the mechanisms. Taking as an example the helmet. If a person only did the practicum, he could think

Country

Overarching themes

Concepts

Training content

Soft skills training

Training transfer

Opportunities to practice

Spain Translate training into practice

All countries Rewarding transfer attempts

Representative quotes (Thought units) that if a weight drops from height, it could kill you, but he does not know that if an electric wire touches you, the helmet could save your life. A person does not think of this because he does not perceive it as an imminent risk” (Italy, Migrant worker) “I think it’s better if it is a bit of both theory and practical. So, it’s better to split it, so like a bit of theory and a bit of practice so when you’ve had theory for a few days you normally forget the first couple of days, but if you do a bit of both it is a bit easier to remember.” (UK, Migrant worker) “Training should not only be technical, but also training in responsibilities, consciousness, sensitization” (Expert, Spain) “It’s your safety and it’s our safety” (UK, Migrant worker) “I think it’s like any training it is the quality of the training and you have got to be able to put that into practice as soon as you get it, otherwise you lose that competence and that is the same with any training. If you have the training and then don’t do it, you soon forget.” (UK, Supervisor) “For me it’s more important to practice, you can’t just read the book. If you don’t try it, how can you learn it? […] Yes, you have to practice. Of course, when you do the practice, you must already have things in tense, this also helps you. If you read nothing.” “I think that rewarding certain safe behaviours is a good formula; we usually punish or admonish, but rewarding could work well.”

Country

All countries

All countries

Italy

Spain

equipment upfront. Similar issues were also discussed by safety experts and trainers in Spain and the UK. Participants from Italy, Spain, and the UK also agreed while principal contractors typically follow safety legislation and receive sanctions for violations, smaller subcontractors (which mainly employ migrant workers) are more likely to flout the rules and not be punished. For example, a UK expert highlighted how principal contractors rely on subcontractors to adhere to safety regulations with the result safety standards become “diluted, diluted, diluted” down the supply chain. This mirrored the views of an expert from Spain who explained “in small companies is where we have more problems, as the majority of the time, safety plans do not work”. Our findings here support previous research, which has discussed how subcontractors are often unaware of legal obligations and/or have limited resources to devote to safety compliance (e.g.,

All countries

7

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Lingard & Rowlinson, 2005; Loosemore, Dainty, & Lingard, 2003).

Europe, demands were also put on supervisors to manage the frag mented safety culture in multicultural construction sites. This mirrors Jaselskis et al. (2008), who highlighted the need for cultural awareness in communications between Hispanic migrant workers and US super visors. A Spanish supervisor suggested:

3.1.2. Discriminatory allocation of riskier work Alongside the above issues with safety training, consistent with the literature (Roelofs, Martinez, Brunette, & Azaroff, 2011), supervisors, trainers and experts from Italy, Spain, and the UK agreed migrant workers are typically discriminated against and given “the dusty, dirty, horrible jobs” (Trainer, UK), which are increasingly dangerous and, thereby, further compromise their safety. Similarly, a supervisor in Italy stated, “From what we see every day, migrant workers usually do lowly hand jobs, usually cargo handlings, porterage, that’s all”, while in Spain, safety trainers and experts reported migrant workers typically occupy the roles of “ferrallista” or “encofradores” (rebar workers or formworkers) as they require less qualifications. For instance, in Spain, workers originating from Africa are reported to always be ‘ferrallistas’. These are physically demanding jobs, with higher rates of accidents compared with other positions. The continual pressure on migrant workers to complete tasks quickly, and forego safety requirements, was highlighted by supervisors, safety experts, trainers, or migrant workers themselves, across all three countries. One migrant worker in Spain recognised “speed is more rewarded than the quality of the work or fulfilling safety norms”, while another migrant worker, also in Spain reported not wearing a safety harness in order work more rapidly; “if you have to go up to the scaffold, only to do a small thing, you do not want to lose time”. These findings reflect previous studies, which consider how pressure to deliver con struction projects on time and on budget results in breaches of safe working practices (e.g., Dutta, 2017; Oswald et al., 2020). A migrant worker in the UK encapsulated the situation: “You can do things the safe way which is slower, or you can do things the fast way. So, things like heights and stepladders; somebody could climb onto the forklift bars and be raised up that way instead and then they are risking falling and going down, so sometimes when the safe way takes a long time, we do things to cut corners to make it quicker”.

“Supervisors must speak two languages: the language of the office and the language of the people of the street […] with immigrants the key aspects are respect and tolerance, and empathy with the rest of the workers.” 3.1.4. Language barriers Concerning migrant workers’ challenges in the construction site, one of the most relevant issues concerns the language. What usually happens is that the migrant worker with the better host language tends to become the group leader and usually translates instructions from supervisor to workers in the group who are from the same country of origin as also identified in the studies by Bust et al. (2008) and Guldenmund et al. (2013). One supervisor in Spain formulated it this way: “What usually happens is that the migrant worker with the better host language tends to become the group leader and usually translates in structions from supervisor to workers in the group who are from the same country of origin.” This results in the fact that managers and or supervisors of migrant workers with lower language skills are not sure whether the messages are being correctly passed on (Bust et al., 2008; Tutt et al., 2011). Moreover, people usually tend to work in groups composed by other people who share the same language, an issue also identified by AlBayati et al. (2017). One safety expert in Spain observed: “People usually tend to work in groups composed by other people who share the same lan guage.” We identified more language barriers related to safety training; they are discussed below.

In line with research suggesting machismo is highly influential over the safety-related behaviours of migrant workers, particularly from Latin American (Chan et al., 2017) an Italian supervisor stated:

3.1.5. Opportunities for promoting safety at work In addition to the challenges to ensuring migrant workers’ safety, our focus groups and interviews already revealed some opportunities for managing migrant workers safety at work. The opportunities include supervisors’ role modelling focusing on soft skills to support technical skills. Supervisors, trainers, and experts across the three countries spoke of the need for effective role-modelling on the construction site. A su pervisor in Italy noted, “if no one wears a helmet, they [migrant workers] also do not use it; if their bosses do wrong manoeuvres, they imitate”, while a trainer in Spain commented “If the supervisor arrives at the workplace in moccasins, the message to all is to remove safety shoes and put on moccasins, but if the supervisor comes totally dressed in PPE, from top to bottom, all the others will do the same”. Another key element of ensuring good safety in the construction site is the use of soft skills. Such skills refer to complementary expertise that enables workers to use their technical skills (Flin et al., 2010). For example, a national worker in the UK raised the importance of being able to communicate about hazards in the workplace and stated:

“In some ethnic groups there is an underlying machismo, which tends to underestimate some dangers. They think, ‘I am a grown man and I do not wear the helmet’. Mainly migrant workers from the East European Countries report a little bit of carelessness due to the fact that they are rough and tough guys”.

“So, if somebody spots a hazard, you go to a supervisor or manager and say: ‘right this needs to be resolved, how can we resolve it?’ and you both talk to each other and decide it this way, or that way, or whatever and to me communication is the biggest safety feature of all, because if things aren’t communicated properly the job doesn’t get done.”

3.1.3. Cultural aspects In agreement with existing literature (Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010), supervisors, experts, or trainers from all three countries attributed migrant workers’ violations of safety rules and regulations to differences in their background experiences and national cultural characteristics. For instance, the typically less strict safety practices with which migrant workers were accustomed in their home countries, were deemed to be the reason behind their poorer perceptions of risk. A supervisor in Spain commented: “There is diversity. There are people who come from countries where the preventive culture is practically invalid and they are very reckless. For them, working with risks seems to be almost always the norm”.

The poor safety awareness is exacerbated as migrant workers have poor knowledge of safety rules and regulations in the host country. Together, these issues make migrant workers vulnerable to exploitation:

3.2. Migrant workers’ safety training challenges and opportunities

“if they [migrant workers] don’t know culturally what level of health and safety to expect on site […] they will just do what they are being asked to do and that may not be good practice” (Trainer, UK).

In relation to research question 2 about the key challenges and op portunities of migrant workers in relation to safety training, our results also point to important findings, both confirming and extending existing research. We identified four key themes in response to this research question: Training provision, language, delivery, content and transfer.

Given the multicultural nature of many construction sites across 8

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

See table 3 for an overview of the analysis.

trainees gave me a blank test sheet […] and then they told me ‘I do not know what is written here, it is not useful that I randomly answer the questions’”. In all countries, training at times relied on ‘trainee translators’, i.e., one of the workers participating in the training with slightly better language skills, to convey safety information accurately during training, site inductions, and daily safety briefings. This was reported to be problematic as it required a great level of trust, neither trainees nor trainers had any means of checking what had been communicated. Our findings support current literature (e.g., Bust et al., 2008; Jaselskis et al., 2008). A safety expert in the UK highlighted how this approach com promises migrant workers’ safety:

3.2.1. Safety training provision Although Italy, Spain, and the UK all have numerous laws and cer tifications relating to mandatory safety training for construction workers (e.g., the Spanish regulations established in the National Collective Agreement), safety trainers and experts in Spain and the UK voiced concerns about the level of training offered by smaller companies. In line with studies highlighting how the devolvement of health and safety responsibility down the supply chain often results in limited safety training for migrant construction workers (e.g., Chan et al., 2010), trainers in Spain discussed the reluctance of some smaller sub contractors to spend money on workers, who are likely to leave for another job after a few days. Therefore, only basic safety training is typically offered. These views were shared by safety experts in the UK; as one explained, an employer may say “well I want you to work, but as you’re self-employed you can pay for that course yourself […] if you don’t, bye bye”. Furthermore, the UK experts described how some smaller subcontractors are so unwilling to invest money that migrant workers often receive no safety training at all, particularly when migrants’ lan guage skills are limited. The lack of provision of training, however, was not only a problem among subcontractors, also in larger organizations was a lack of safety training provision a problem as it was not always monitored in every country who had been trained in the use of different equipment, and there was no control as to whether those that used the equipment had been trained. A migrant worker in the UK reported:

“So on inductions, we will induct everybody onto our site, and we’ll induct them in English, and then we will expect the translator to then translate what we’ve spoken to those individuals. That induction can last, what, half an hour I’d say? Is he passing that information across? He’s probably passing 10 min of that half an hour induction across to that individual. So even on the basics of inducting that individual onto site, and getting him aware of what our site constraints are, our site issues, our site risks, etc. Are we properly passing it over to him? Probably not.” The problem, however, was less in Spain than Italy and the UK. Nine out of the 10 construction workers interviewed in Spain did not feel language presented a barrier either to the safety of their work on site or to safety training, which was always delivered in Spanish. This may be a reflection of the sample composition; of the seven migrant workers who participated in Spain, all had been in the country for at least 10 years and three had been in the country for over 20 years, so they are likely to have a good grasp of the language. Moreover, Spanish was the first language of participants from Latin America (e.g., Ecuador). This is unlike migrant workers in Italy and the UK where migrant workers do not come from a country which shares the language with the host country. One native worker said:

“I’ve had training on the scissor lift and moving vehicle training, crimping training; that is connecting pipes so you have two parts connecting them and you are just crushing them together. I have been waiting for electric pallet training for three years, it is cheap to do, at first everybody could use it but now only two people can use it. People have had the training, so I’ve been waiting three years for the training for that. I think that is really stupid because it slows you down on your jobs. So you can still use it without training but it’s not good health and safety behaviour.”

“We do not have problems with language because many times the mother tongue of migrant workers is Spanish, and if they come from other countries (for example from Africa), they already know some Spanish.”

Finally, the dangers of singling out and creating special training for migrant workers was seen to have the potential to create tensions in the workplace. One safety expert in the UK formulated it this way:

3.2.3. Training delivery Additionally, methods of training delivery are not always appro priate for facilitating positive safety outcomes. Consistent with existing ´ et al., 2020; Sokas, Jorgensen, Nickels, Gao, & research (e.g., Peiro Gittleman, 2009), participants from all three countries advocated the importance of practical, hands-on safety training, providing migrant workers with opportunities to apply their theoretical learning in a realworld context. For instance, a supervisor in Spain commented, “In situ, they [migrant workers] see the risks better”, and a native worker in Spain explained: ”It’s just that on site you learn things better than in the class room”, while a supervisor in the UK agreed demonstrating safety be haviours on site enables “a huge gap in potential misunderstanding to be closed”. Even when training took place in the classroom, combining theory and practice was reported to be important as practical exercises were trained workers then remembered the material better. A UK migrant worker explained:

“You only need to look at the differences between the migrant workers and the native workers, so that’s your solutions, govern, those differences to bring them at the same level as native workers. Otherwise, there will be a conflict because you’re treating them more or you, you will be seen to care about them a lot more than native workers. So by inventing training schemes, you’re separating people. Of course, because you’re differenti ating people. You don’t want to do that because you causing division in the construction industry. Ah, yeah. But we’re better than you so we have to go train him every three months free of charge and we get paid for it, whereas you have to work, you know what I mean? And it will cause a conflict.” 3.2.2. Training language When safety training does occur, language barriers are also reported to hamper migrant workers’ learning and, subsequently, training effectiveness (e.g., De Souza et al., 2012; Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010). One particular barrier was that training was available in the native language only in Italy and the UK in particular. One migrant worker in the UK reported how he struggled with jargon:

“Usually, it starts with the theory but it depends on the training, but usually it is theory first, then a short test and then you go to practice. So on the shopfloor they know how to do it so they can probably look at some pipes or whatever it is they are doing. I think the last training I was there for was the electric power truck and there are some barriers, so you have to go around the barriers in the truck and then you have to put stuff up in the truck, so it’s like practice training…: I think it’s better if it is a bit of both theory and practical. So, it’s better to split it, so like a bit of theory and a bit of practice so when you’ve had theory for a few days you normally forget the first couple of days, but if you do a bit of both it is a bit easier to remember.”

“You know it was a bit difficult to understand because before I didn’t know what PPE was. I have seen lots of times in some papers PPE and I’m thinking what is this? It is not easy a lot of this.” A trainer from Italy described how migrant workers’ lack of Italian meant they were unable to complete a knowledge test; “Several of the 9

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

Understanding the reasoning behind required safety behaviours, e.g., why wearing PPE is important, was also reported to be helpful for educating migrant workers in host country rules and regulations, thus facilitating sensemaking of why safety is important. A migrant worker in Italy acknowledged:

“I think that rewarding certain safe behaviours is a good formula; we usually punish or admonish, but rewarding could work well.” 4. Discussion

“when things have been explained to me from a theoretical point of view, I started to understand the mechanisms. Taking as an example the helmet. If a person only did the practicum, he could think that if a weight drops from height it could kill you, but he does not know that if an electric wire touches you, the helmet could save your life. A person does not think of this because he does not perceive it as an imminent risk.”

The present study aimed to identify the main challenges and op portunities of migrant workers in the construction industry of three European countries (Italy, Spain and UK) describing the main safety conditions and the factors contributing to an effective implementation of safety training for them. We pointed out relevant antecedents to prevent accidents and injuries among this group of workers, through training migrant workers in safety. Consistent with calls to depart from positivist approaches in construction research (e.g., Phelps & Horman, 2010; Zou et al., 2014), we conducted a template analysis of semi-structured in terviews from four occupational groups: migrant and native construc tion workers, site supervisors, safety experts, and safety trainers. Their contributions provided us with rich insights that allowed us to answer two important research questions. The first research question concerned the key challenges and opportunities migrant workers face relating to safety in the construction sector. In support of previous studies, we found that challenges relating to the structure of subcontracting meant that safety responsibility was often diluted as small contractors were less compliant with safety regulations. As previously identified in the liter ature, migrant workers often lacked job experience working in the in dustry, were allocated the most dangerous jobs, and accepted these jobs due to their precarious situation. Migrant workers’ safety norms and attitudes were often machismo and language barriers often presented a problem. Contrary to the findings in the existing literature, the issue of language barriers was less prominent in Spain where migrant workers often originated from Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. The existing research has predominantly focused on the challenges of migrant workers’ safety, however, we found that supervisors’ role modelling and the application of soft skills such as communication were found to be effective tools in promoting migrant workers’ safety. Our second research question focused on identifying the key chal lenges and opportunities concerning migrant workers’ safety training that exist in the construction sector in the three European countries studied. We identified similar challenges to those reported in the liter ature concerning cultural awareness of safety norms and language bar riers, with the exception of Spain where our interviewed workers had been working in Spain for a number of years and often originated from Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. In terms of opportunities for effective safety training, we identified hands-on training and opportu nities to practice and in particular opportunities to apply acquired skills and knowledge once migrant workers returned to the construction site, i. e. training transfer. Our participants also reported that training in soft skills to support the use of technical skills was important to ensure training transfer.

A similar comment was made by a UK migrant worker: “I think it’s better if it is a bit of both theory and practical. So, it’s better to split it, so like a bit of theory and a bit of practice so when you’ve had theory for a few days you normally forget the first couple of days, but if you do a bit of both it is a bit easier to remember.” 3.2.4. Training content Equally important to the training delivery is the content of training. A key issue discussed by construction workers, supervisors, experts, and trainers, in Italy, Spain, and the UK, was the need for safety training to cover ‘soft’ skills, i.e. skills that support technical skills such as use of PPE and safety risks and hazards. That is, educating migrant workers about the importance of working with colleagues to create a sense of shared responsibility - “it’s your safety and it’s our safety” (Migrant worker, UK) - and the need to be aware of, and communicate about, hazards on the construction site. For example, an expert from Spain stated, “Training should not only be technical, but also training in re sponsibilities, consciousness, sensitization”, while a trainer from Italy noted, “As in sports teams, we need to teach them how to be a team, to work as a crew”. Knowledge and understanding of soft skills like these are crucial for enhancing the safety of migrant construction workers (e.g., Harrington et al., 2009; Vignoli et al. 2021), although are rarely included in training (Peir´ o et al., 2020). Given the multicultural nature of many construction sites across Europe, concerns were also raised about the importance of sensitivity training, to make all workers aware, and accepting of, cultural diversity. This mirrors Jaselskis et al. (2008), who highlighted the need for cul tural awareness in communications between Hispanic migrant workers and US supervisors. 3.2.5. Training transfer A theme that has not been covered much in existing research is the extension of the practice element of training delivery to training transfer, i.e., the extent to which workers return to the workplace and have the opportunity to apply and practice what they have learned. One UK su pervisor explained it this way: “I think it’s like any training, it is the quality of the training and you have got to be able to put that into practice as soon as you get it, otherwise you lose that competence and that is the same with any training. If you have the training and then don’t do it, you soon forget.”

4.1. Key contributions of the study In this way, our paper makes four key contributions to existing knowledge of migrant construction worker safety. First, our multidis ciplinary literature review reveals the majority of research has been conducted in the US (with Hispanic and Latino migrant workers, with few studies in a European context (for notable exceptions see Bust et al., 2008; Guldenmund et al., 2013; Oswald et al., 2017). The results from our study indicate several similarities and differences on the issues considered when focusing on Italy, Spain and the UK. In fact, we have confirmed that a number of important factors about working conditions in other regions of the world also occur in these countries while also we have found some new aspects that were not reported in previous studies. Second, our analysis has adopted a qualitative approach especially because it was our aim to better understand the interpretations of different relevant actors. In fact, our study went beyond the views of the

The ability to translate training into practice is also emphasized by an Italian worker in this way: “For me it’s more important to practice, you can’t just read the book. If you don’t try it, how can you learn it? […] Yes, you have to practice. Of course, when you do the practice, you must already have things in tense, this also helps you. If you read nothing and know nothing, when you practice, you cannot manage to the end what has to be.” To ensure migrant workers are encouraged to transfer knowledge about good safety behaviours a Spanish trainer suggested rewarding migrant workers may be an effective strategy to ensure training transfer: 10

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

4.2. An integrated picture of the main challenges identified both on the safety conditions and safety training for construction migrant workers in Italy, Spain and UK

workers on the matters studied. We considered the interpretations of the challenges affecting migrant workers’ safety amongst relevant stake holders that play a key role in ensuring migrant workers’ safety in the construction site. Their views provide a rich and complex interpretation of the migrant worker safety issues in the countries studied. Based on the sensemaking theory as our underpinning framework (Weick, 1995), we analysed how different significant actors gave meaning and interpreted their experiences. This interpretation is extremely valuable because it influences individual and collective behaviours and the attitudes and the actions put in place by the different occupational groups involved. Previous studies in the three countries have either focused on native workers’ perception of their migrant colleagues (Briscoe et al., 2000), migrant workers (Dainty et al., 2007a; Hare et al., 2013; Tutt et al., 2011) or on a combination of safety experts and supervisors (Oswald et al., 2019). To the best of our knowledge, the perspectives of safety trainers have not previously been explored in these three countries. Third, previous studies have typically focused on a single construction site in one country. In contrast, our research contributes to this body of knowledge by investigating the determinants of migrant workers’ safety on sites in Italy, Spain and the UK. In all three countries, the labour force was more heterogeneous (e.g., Eurostat, 2019; ONS, 2018) than in the majority of previous research. Our study comprised construction workers from numerous countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Ecuador, Estonia, India, Ireland, Kosovo, Latvia, Moldova, Morocco, Portugal, Romania, Tunisia and Turkey) speaking many different languages, working across multiple construction sites thus providing more generic knowledge than in previous qualitative studies in the UK context (Oswald et al., 2017, 2020; Tutt et al., 2011). Fourth, we paid special attention to the challenges and opportunities of training to ensure safety in the construction site (Guo et al., 2012). Training migrant workers in the construction sector is critical as this group is especially vulnerable, given the number of accidents. In the ´ et al. (2020) none of the 18 studies systematic literature review by Peiro ´ et al. in the review had been conducted in Europe. Furthermore, Peiro (2020) concluded that safety training of migrant workers in the con struction industry is far from effective. In the present study, we explore the factors that safety professionals, trainers, supervisors and the workers, perceive to be important to deliver an effective training of migrant workers in the construction sector. Importantly, sensemaking theory is not only about undesirable phenomena. Louis and Sutton (1991) emphasised the importance of exploring sensemaking of positive phenomena and in our study, we focused also on what key stakeholders perceived might improve safety training effectiveness for migrant workers.

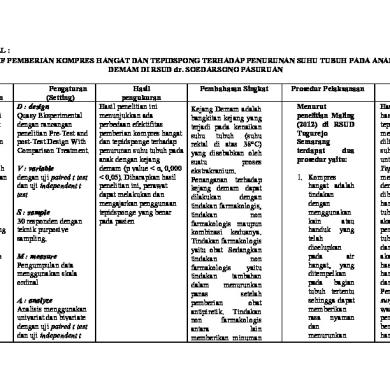

In Fig. 1, we summarised the final themes and their hierarchy separating the migrant workers’ safety opportunities and challenges from the safety training challenges and opportunities for this group of workers. The countries in which the study was performed and the main perspectives considered to analyse the phenomena under study are also presented. 4.2.1. Safety conditions Our results replicate and confirm the main themes identified in previous studies carried on in other countries. Similar to previous studies (e.g., Buckley et al. 2016; Chan et al., 2010; Dainty & Chan, 2011) supervisors, safety experts, and trainers from Italy, Spain, and the UK reported outsourcing of work to subcontractors employing migrants with poorer language skills and limited experience of construction was commonplace. Safety experts and trainers in the UK and supervisors in Italy highlighted how migrant workers often experience low pay (e.g., Dainty et al., 2007a). One migrant worker in Italy also reported an instance of wage theft (e.g., Fussell, 2011). Trainers, safety experts or supervisors from Italy, Spain and the UK reported safety is diluted down the supply chain (Dainty & Chan, 2011; Loosemore & Andonakis, 2007). Safety experts in the UK and Spain highlighted whilst principal con tractors follow safety legislation and are fined for breaches, sub contractors are often unaware of their obligations or do not commit resources to comply with legal requirements (Lingard & Rowlinson, 2005; Loosemore, et al., 2003). Supervisors, safety experts, and trainers from Italy, Spain, and the UK reflected on migrant workers often being given the more “dangerous’’ and “dirty” jobs than their national co-workers (Roelofs et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2010). For example, in contrast to existing literature, there was a difference of opinion between our participants in terms of task allocation. Many supervisors, experts, and trainers in Italy, Spain, and the UK agreed migrant workers were typically given the riskier tasks, whereas construction workers in Italy and Spain (migrant and national) and the UK (national) did not perceive any differences. Again, echoing previous research (Dutta, 2017; Oswald et al., 2020), supervi sors, safety experts, trainers, or migrant workers from Italy, Spain, and the UK, described how migrant workers were more willing to breach safety regulations to meet tight deadlines. Such safety violations, and poor safety-related attitudes and behaviours, were attributed to national cultural characteristics and differences in home-country experiences by

Fig. 1. Overview of the final themes and their hierarchy analysed in the three countries considering the views of four relevant stakeholder groups. 11

R. Shepherd et al.

Safety Science 142 (2021) 105388

supervisors, experts, or trainers from all three countries (Menzel & Gutierrez, 2010; Oswald et al., 2018). For instance, in line with studies of workers from Latin American cultures (Choudhry & Fang, 2008; Robertson et al., 2007), migrant workers’ reluctance to wear PPE was reported by supervisors and trainers in Italy to be due to machismo. The innovative multi-perspective approach in our study has provided new information that is helpful for the professionals involved in improving safety conditions for migrant workers. Two main strategies have been mentioned and analysed in detail. One concerns the impor tance of role modelling as a basic mechanism to promote safety at work and the other is the use of soft skills such as communication, team work, raising awareness, etc. as a way to enhance behaviours and attitudes conducive to safety behaviors in migrant workers.

supervisor are essential for migrant workers to enhance training effec tiveness in the workplace. Finally, a Spanish trainer suggested that carrot rather than stick may facilitate migrant workers’ transfer of ac quired skills and knowledge, i.e. reward for working safely rather than punishment for not working safely. To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study has studied the importance of training transfer among migrant workers (Hussain et al, 2020). 4.3. Limitations Notwithstanding the contributions of our study, there are limita tions. The composition of our sample is likely to have influenced our findings. The majority of our migrant workers had been resident in either Italy, Spain, or the UK for at least 10 years, meaning they are likely to have acclimatised to the host country’s cultural norms and developed a good level of English, Spanish or Italian. Furthermore, we received feedback when we presented our preliminary findings, we are unlikely to have captured the interpretations of the most vulnerable members of the workforce (i.e., those who have very limited language skills and/or whose immigration status is precarious). As we discussed at the outset of this paper, within the construction literature, workers are typically categorised as migrant or non-migrant, based on their birth location. This does not consider the length of time a worker has been resident in a country, whether they have become a national of that country, or even if they consider themselves to be ‘migrants’. In addi tion, the focus group and interview methods do not fully prevent that answers could be influenced by social desirability. Nevertheless, confi dentiality was assured in every occasion to promote a psychological safety climate and their true responses. In the focus groups, the dis crepancies between participants were also a mechanism to “discount” biases. In the template analysis, we also paid attention to this issue. Finally, the methods used are limited in terms of providing a precise measurement of sense making, nevertheless, as we pointed out in the introduction, in our study sensemaking is used more loosely to explore how key stakeholders make sense of discrepancies in workers safety and the ways they respond to training depending on their national status. In this context, the methods used were useful to identify the participants’ mental models and their similarities, although a richer methodological approach could be considered in future research.